Chapter 6

Stochastic Environments

We have discussed about the agent’s behavior, and action in a deterministic environment. Remember, we had $S$ states, $A$ actions and Transition model $T (s, a)$, i.e., we knew agent will definitely take action $a$ at state $s$. But, in real world, that is not always the case; for example in the mopping bot example that we had discussed earlier in section 1, the actuators are physical objects, one can’t be fully sure about them. In stochastic environment, we have to associated a $Reward$ function with every state. The $Reward$ function $R : states \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is a mapping of states to a real number which serves as a reward for the agent. Its role is similar to a cost function $C : states × actions \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ for the case of deterministic environment. However, there are certain subtle differences. The agents in stochastic case seeks to maximize rewards rather than minimize cost. Also, the reward function does not take an action as an input, due to its stochastic behavior of actions.

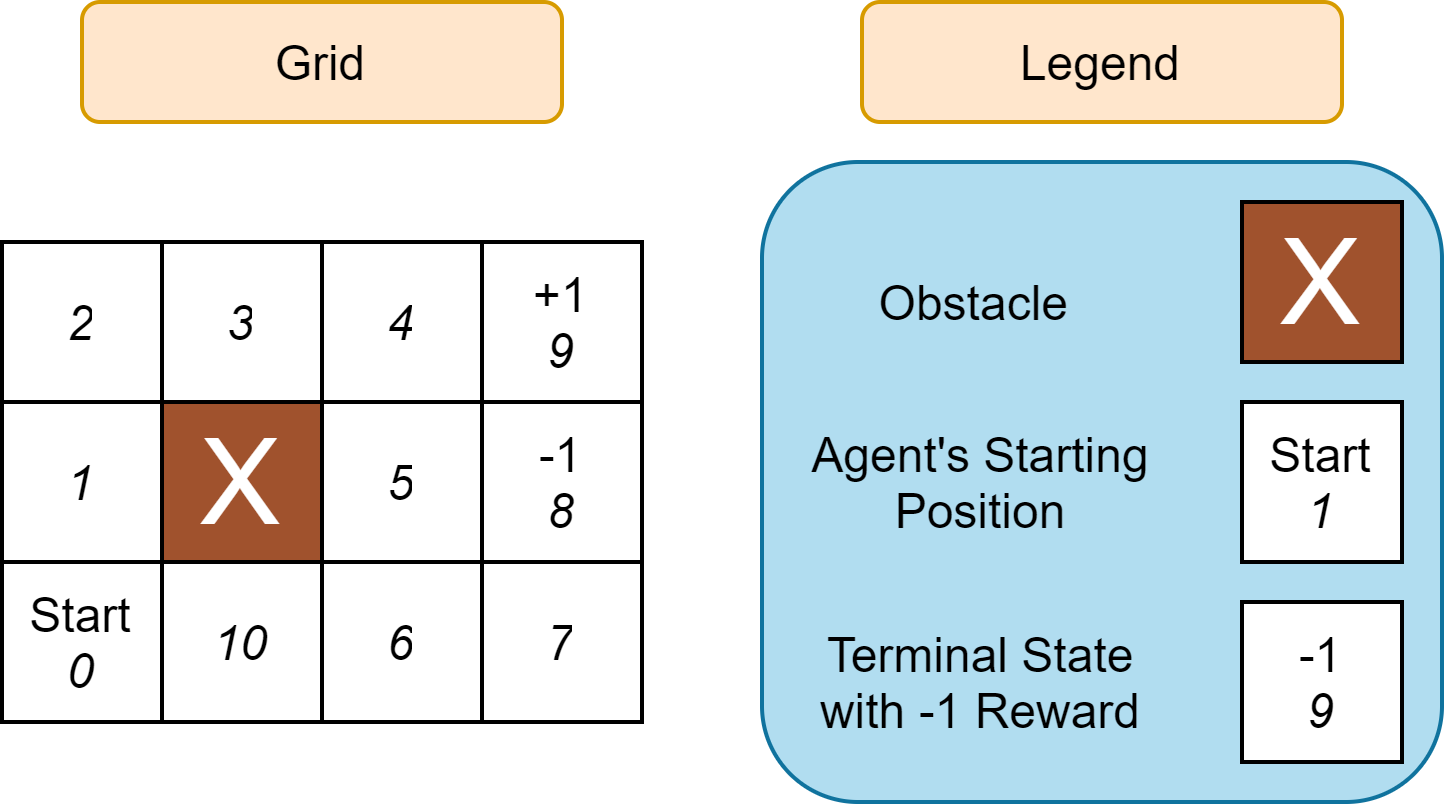

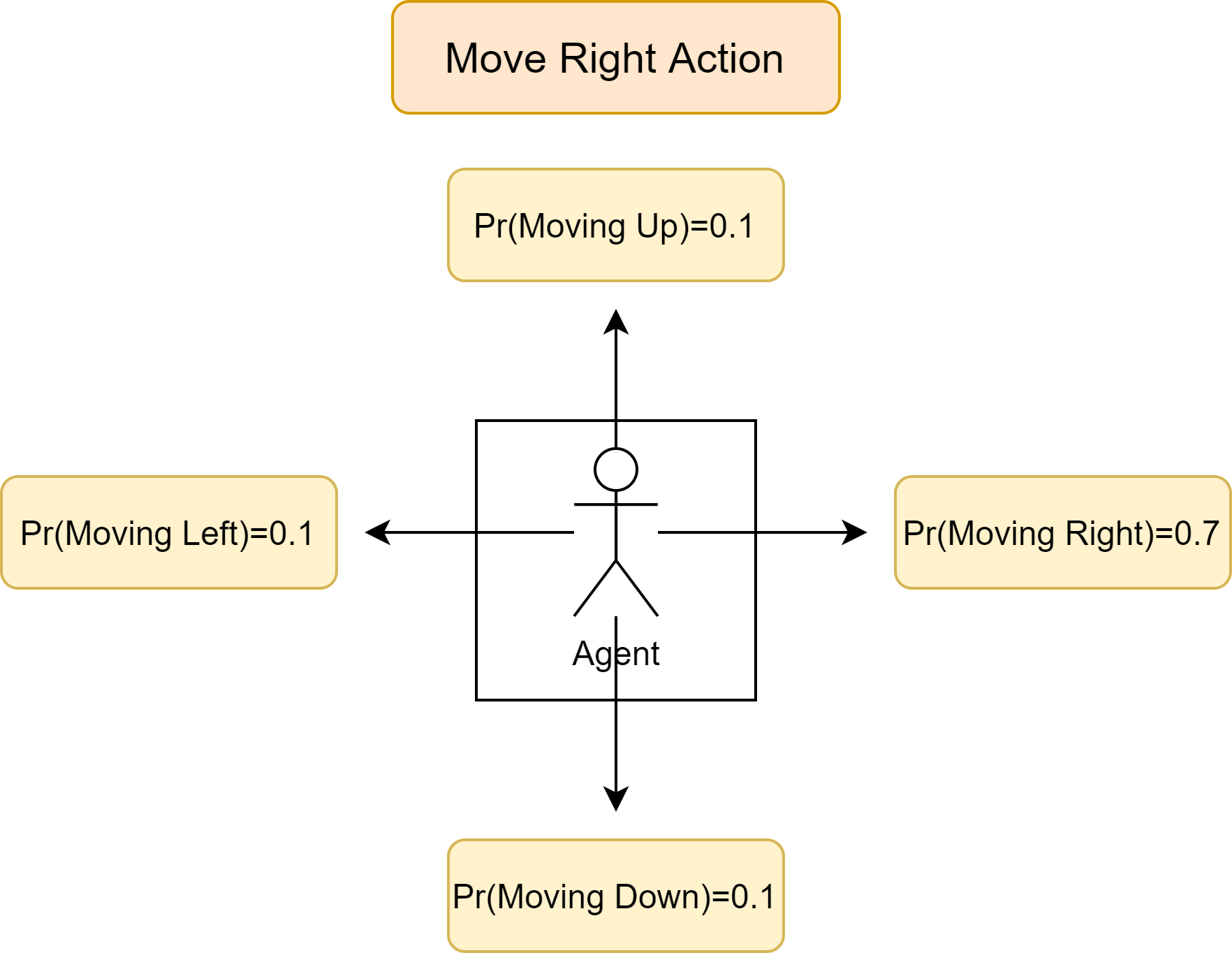

Let us consider an example: suppose we have an agent situated in a 3 × 4 grid (Figure 20), and we assume that the environment is fully observable from the grid. The agent starts off at square 1, and the game terminates when the agent reaches square 9 or 10. The actions are provided by an action function $A(s)$ at the location square s, and the possible actions that can be taken are $Up$, $Down$, $Left$ and $Right$. Consider the environment that every time agent move towards intended direction, it can also go in either side with equal probability 0.1. So far, in deterministic environment, we were concerned with planning, i.e, how to go from start to goal, however, now we can not be sure that once we had taken an action, we will reach the next desired state. The goal of the agent is to maximize its utility based on some reward function $R(s)$ until the game ends.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 20: 3 × 4 Grid Environment | Figure 21: Probability outcomes for an intended $Right$ move |

Let us try to model agent’s behavior for above discussed example:

States, s: The various states in above described game are simply the various possible positions that the agent can be on the grid. This comprise of all the numbered positions on the grid in Figure 20, less the position of the obstacles. The state at which the agent is a position square $i \in [0, 10]$ is denoted as $s_i$ in lower case.

Actions, A(s): The agent can take one of four possible action at any given state $s: A(s) \in {Up, Down, Left, Right}$ for any state $s$. However, now it is not guaranteed that the agent will transition to the intended outcome by moving in the intended direction.

Transition Model, T(s,a): The transition model takes in the current state and an action as the input, and returns a probability distribution over all the possible states the agent will transition upon with action $a$ in state $s$. Here, we have a probability of 0.7 of moving in the intended direction, and probability of 0.1 of moving in one of the other three direction; Figure 21 shows the case of moving $Right$. If moving in a direction is illegal (say moving into an obstacle or out of the grid), the agent remains at the current position. For example, suppose the agent is at position S0 (square 0) on the grid and chooses to move Up. Then the transition model returns the following, where $s’$ represents the neighboring state of $s$:

\[T(s=s_0,a=Up) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0.7 & \mbox{if $s'=s_1$;} \\ 0.1 & \mbox{if $s'=s_{10}$;} \\ 0.2 & \mbox{if $s'=s_0$;} \end{array} \right.\]In essence, the transition model returns $P(s’|s,a)$, which means the conditional probability that the next state will be s’ conditioned on the current state $s$ and the agent’s action $a$.

Reward Function, R(s): Assume for the rewards function, we have the following mapping:

\[R(s) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} +1 & \mbox{if $s=s_9$;} \\ -1 & \mbox{if $s=s_8$;} \\ -0.4 & \mbox{if $s \notin \{s_8,s_9\}$;} \end{array} \right.\]The mapping above simply means that for terminal state $s_9$, the reward is 1, but for terminal state $s_8$, the reward is -1. For all other states, the reward is −0.4.

Initial State: The initial state s0 is simply square 0 labeled as “Start” in the Figure 20.

Goal: There may not be any specific or permanent goal state for the agent in this example. Therefore, it is best that the goal of the agent be left “flexible”. The agent will primarily be utility based, planning its actions so as to maximized its expected utility rather than to reach one specific goal.

Terminal States: There are two terminal states (locations) in the grid, square 8 and square 9, represented by $s_8$ and $s_9$ respectively. The game ends upon reaching those terminal states.

Defining a sequence of actions for the Agent

In a deterministic world, a plan can simply be defined as a sequence of action that will lead to a deterministic outcome at the end. If the game was deterministic, one of the viable solution to maximize rewards will be the following sequence of actions.

\[\mbox{Actions: }Up, Up, Right, Right, Right\]And, the outcomes along the above following sequence of actions would be:

\[\mbox{Path: } s_0, s_1, s_2, s_3, s_4, s_9\]Thus reaching the terminal state with positive rewards $s_9$ with minimal steps(that reduces the reward). However, in when the transition model is stochastic, reaching the outcome with above stated aforementioned plan has a very small probability, in particular less than $0.2$.

\[\mbox{Pr(Reaching $s_9$ from $s_0$ with above plan)}=0.7^5 = 0.16807\]This is because at every state along the intended path, there is a significant probability of veering off course. For example, at $s_0$, there is a chance of $0.1$ of landing on $s_{10}$ and $0.2$ chance of remaining at $s_0$ rather than moving to the intended $s_0$. Therefore, for stochastic model, a plan cannot just be a sequence of actions.

7.1 Defining a Policy as a Plan

We have to define a $policy$ for the agent that plans for all possible contingencies. A policy $\pi : states \mapsto Actions$ is a function that maps all possible states that the agent could end up in to an action.

One possible policy could be the following:

\[\pi (s) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} Up & \mbox{if $s \in \{s_0, s_1, s_5, s_6, s_7\}$;} \\ Right & \mbox{if $s \in \{s_2, s_3, s_4, s_{10} \}$;} \\ \end{array} \right.\]This policy attempt to head $Up$ and to the $Right$ at every opportunity to reach the terminal state $s_9$ with the $+1$ reward. Due to the stochastic behavior of actions, there are many possible sequence of states $\tau$ that could be observes if the agent acted according to the above policy. Some examples are,

\(\tau_1 : s_0, s_1, s_2, s_3, s_4, s_9\) \(\tau_2 : s_0, s_{10}, s_6, s_7, s_6, s_5, s_4, s_3, s_4, s_5, s_4, s_9\) \(\tau_3 : \cdots\)

7.2 Utilities for Policies

Since, we can have different policies, we need a way to compare them. We need a $utility$ function for each policy, which returns the expected utility value for state $s$ with a given policy

Firstly, we need a sequence of states $\tau$. $\tau$ could represent a finite sequence of states, or possibly an infinite sequence of states. For example,

\[\begin{align*} \tau_{n} = [s_0,s_1,s_2, \cdots , s_n] \\ \tau_{\infty} = [s_0,s_1,s_2, \cdots] \end{align*}\]Let $U_h(\tau)$ be the utility for a given sequence of states $\tau=[s_0,s_1,s_2, \cdots , s_n]$ that we observe.

There are can be two defining characteristic of the utility function $U_n$. First, it can be additive of all the rewards provided at each state.

\[\begin{align*} U_h(\tau) &= U_h\left([s_0,s_1,s_2, \cdots , s_n]\right) & \\ &= R(s_0)+R(s_1)+R(s_2)+\cdots & (Additive) \\ \end{align*}\]Secondly, it can discount the rewards of later states by a discounting factor $\gamma\in (0,1)$.

\[\begin{align*} U_h(\tau) &= U_h\left([s_0,s_1,s_2, \cdots , s_n]\right) & \\ &= R(s_0)+\gamma R(s_1)+\gamma^2 R(s_2)+\cdots & (Discounted) \end{align*}\]This may serve to represent a certain degree of impatience in the agent, in that the same reward now is worth more than the same reward later in the future. The further away in time, the less significant the reward is to the utility. However, the key advantage of applying a discount function is that it makes the utility easier to compute for cases where there is an infinite sequence of states. The discounting factor allows for the convergence of utility to a specific finite value.

In particular, suppose that the rewards function is bounded above by some finite number $R_{max}$. Then, $\forall s_i\,\, R(s_i)\leq R_{max}$. Moreover,

\[\begin{align*} \forall \tau \, \, \, U_h([s_{i_1},s_{i_2}, \cdots])&= \sum \limits_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma R(s_{i_t}) \\ &\leq \sum limits_{t=0}^{\infty} R_{max} \\ &= \frac{R_{max}}{1-\gamma} \end{align*}\]That means for all sequence of state $\tau$, even for infinite ones, $U_n$ is bounded above by some finite value.

However, we still have a problem with the current way the utility is defined, because a policy $\pi$ does not guarantee a deterministic sequence of states $\tau$. So we are going to introduce some random variables: \(S_t: \text{The state reached at time t}\) We define the utility for each policy as the \textit{expected} utility for the current state $s$ for a given policy $\pi$, denoted $U^\pi$.

\[\begin{align*} U^\pi (s)&=E[U_h(\tau)] \\ &=E\left[\sum \limits_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t R(S_t)\right] \end{align*}\]With this utility $U^\pi$, we can compare policies to pick the one that is most preferred at the current state $s$. The optimal policy at state $s$ can be defined as such,

\[\pi^*(s)= \arg \max \limits_\pi U^\pi (s)\]Note that optimal policy is independent of start state; it only depends on current state $s$. This is also the reason why we defined the notion of policy from $states \mapsto action$ instead of a sequence of state mapping to action. We can also define the optimal policy another way, in terms of its actions that was mapped from a state.

\[\pi^*(s)= \arg \max \limits_{a\in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U^{\pi^*}(s')\]where $A(s)$ refers to actions available to the agent at state $s$ and $s’$ refers to the possible neighbouring states of $s$. The equation above simply means that the agent in implementing the optimal policy, should select action that maximizes its expected utility of the subsequent possible states.

To simplify the notation, let $U(s)=U^{\pi^*}(s)$. Then, \(\pi^*(s)= \arg \max \limits_{a\in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U(s')\)

7.3 Bellman Equation for Utilities

Next, we attempt to define the utility in terms of the direct relationship between the utility of a current state and the utility of its immediate neighbours. This method of definition is also called the Bellman equation.

\[\begin{align*} U(s)&=E\left[\sum \limits_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R(S_t)\right] \\ &=E\left[ R(S_0) + \sum \limits_{t=1}^\infty \gamma^t R(S_t) \right] \\ &= R(s) + E\left[ \sum \limits_{t=1}^\infty \gamma^t R(S_t|S_0=s) \right] \\ &= R(s) + \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|S_0=s, \pi^*(s)) \sum \limits_{t=1}^\infty \gamma^t R(S_t) \\ &=R(s) + \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|S_0=s, \pi^*(s)) \left[ \gamma R(s') + E\left( \sum \limits_{t=2}^\infty \gamma^t R(S_t|S_1=s') \right) \right] \\ &= R(s) + \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|S_0=s, \pi^*(s))\gamma \left[ R(s') + \sum \limits_{t=2}^\infty \gamma^{t-1} E\left( R(S_t|S_1=s') \right) \right] \\ &= R(s) + \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|S_0=s, \pi^*(s))\gamma \left[ R(s') + E\left( \sum \limits_{t'=1}^\infty \gamma^{t'} R(S_t|S_1=s') \right) \right] \\ &= R(s) + \gamma \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|S_0=s, \pi^*(s))U(s') \,\,\, \because U(s')= \left[ R(s') + E\left( \sum \limits_{t'=1}^\infty \gamma^{t'} R(S_t|S_1=s') \right) \right] \\ &= R(s) + \gamma \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s, \pi^*(s))U(s') \\ &=R(s)+ \gamma \max \limits_{a \in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U(s') \end{align*}\]The Bellman equation for utilities as seen from the equation above, states that the utility of a state is the immediate reward for that state plus the expected discounted utility for the next state, given that the agent chooses optimally. Thus we can write the expression of the utility of all $n$ possible states in the game using the recursive Bellman equation. The Bellman Equation for utilities can be interpreted as the utility of the current state, is the sum of the current state rewards plus a discounted expected future utility when the agent plays optimally.

But the problem here is solving the equation to determine the numerical value of a utility is less straightforward, because the $\max$ operator in the Bellman equation is non-linear, and cannot be solved using linear algebra. Therefore, we need algorithms that can closely approximate the utilities ($U(s)$) of all states $s$.

7.4 Value Iteration

The algorithm 23 is as given below, where the input is $problem$, and an acceptable error threshold $\epsilon$. The $problem$ has a set of states $S$, set of actions for each state $A(s)$, a transition model $P(s’|s,a)$, reward function $R(s)$, and discount factor $\gamma$. The ValueIteration function returns the estimated optimal utilities for each state $s$ within a tolerable margin of error $\epsilon$. The main recipe is to initializes all utilities to some value, say $0$. Let $U_i(s)$ be the utility of state $s$ at iteration $i$. Then for each following iteration, $U_{i+1}(s)$ updates in the following way, \(U_{i+1}(s) \leftarrow R(s) + \gamma \max \limits_{a \in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U_i(s')\) The updating keeps iterating on until for all states $s$, $|U_{i+1}(s)-U_i(s’)|$ is within a small tolerable threshold $\delta$.

Algorithm 23 ValueIteration($problem, \epsilon$)

- $U’$ $\leftarrow$ EMPTYDICTIONARY()

- for each state $s$ in STATES($problem$) do

- $~~~~~ U’[s] \leftarrow 0 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \text{// Initialize to }0$

- $\delta$ $\leftarrow$ $\infty$

- while $\delta \geq \epsilon(1 - \gamma)/\gamma$ do $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \text{// Above threshold}$

- $~~~~~ U \leftarrow \text{COPY}(U’) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \text{// Can swap } U \text{ and } U’ \text{ for better efficiency}$

- $~~~~~ \delta \leftarrow 0$

- $~~~~~$ for each state $s$ in STATES($problem$) do

- $~~~~~~~~~~ U’[s] \leftarrow R(s) + \gamma \max \limits_{a \in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s’} P(s’|s,a)U[s’]$

- $~~~~~~~~~~ \delta = \max \left(\delta \, , |U’[s]-U[s]|\right)$

- return $U’$

If we apply an infinite number of iterations, then the estimated utility in $U’(s)$ will eventually converge to a unique equilibrium value where the final utility is the solution to the Bellman equations.

\[\lim \limits_{i\rightarrow \infty} U'(s) = U(s)\]Recall that $U(s)$ is also the shorthand for $U^{\pi^*}(s)$, so the estimated utility will converge to the value of the utility if the optimal policy was implemented. Once we have the utility computed, we can define the optimal policy to be computed the following way,

\[\pi^*(s)= \arg \max \limits_{a\in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U(s')\]7.5 Policy Iteration

An alternative way to get the optimal policy is through the Policy Iteration algorithm. The algorithm 24 takes in a $problem$, and returns the optimal policy $\pi^*$. The $problem$ has a set of states $S$, set of actions for each state $A(s)$, a transition model $P(s’|s,a)$, reward function $R(s)$, and discount factor $\gamma$.

Prior to any iteration, the policy $\pi$ is initialized as a dictionary with some arbitrary mapping of all states in the problem to some action. With a given policy $\pi$, the Bellman utility equation can be simplified to remove the $\max$ component of it. As with a specified policy, there is exactly one action to take for any given state $s$. Thus, there is no need to choose an action that will maximize the utility in the future. This reduces the Bellman equation to a linear equation of utilities from various states. Suppose the policy at the current iteration is $\pi_i$, then the Bellman equation becomes,

\[U^{\pi}(s)=R(s)+\gamma \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s, \pi[s]) U^{\pi}(s')\]By iterating through the various states, and generating a linear equation of utilities from different states, we generate a system of linear equations, of $n$ equations, where $n$ is the number of states in the problem. The linear system can then be solved via Gaussian Elimination to get the utility value for each state in $O(n^3)$ time. With the utilities determined for the current policy, we can then determine the optimal policy for the next iteration, $\pi_{i+1}$ based on this utility.

\[\pi_{i+1}(s)=\arg \max \limits_{a\in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s'} P(s'|s,a)U^{\pi_{i}} (s')\]This loop iterates until the terminating condition is reached, that is, there is not change in policy from iteration $i$ and $i+1$. Then the optimal policy $\pi$ is returned.

In fact, it can be shown that if the algorithm is allowed to iterate to infinity, the equilibrium result will converge to a single optimal policy $\pi^*$

\[\forall s \in S \, \lim \limits_{i \rightarrow \infty} \pi_i (s) = \pi^*(s)\]However, the time complexity of doing Gaussian elimination may make this method unfeasible in solving problem that have a large number of states to account for. The algorithm 24 represents the policy-iterations.

Algorithm 24 PolicyIteration($problem$)

- $\pi \leftarrow$ ArbitraryPolicy($problem$)

- $hasChanged$ $\leftarrow$ true

- while $hasChanged$ do

- $~~~~~$ $linearSystem$ $\leftarrow$ EMPTY()

- $~~~~~$ for each state $s$ in STATES($problem$) do

- $~~~~~~~~~~ linearSystem\text{.add}(U^{\pi}(s)=R(s)+\gamma \sum \limits_{s’} P(s’|s, \pi[s]) U^{\pi}(s’))$

- $~~~~~ U \leftarrow \text{SOLVELINEARSYSTEM}(linearSystem) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \text{// Utilities for each state }O(n^3)$

- $~~~~~$ $hasChanged$ $\leftarrow$ false

- $~~~~~$ for each state $s$ in STATES($problem$) do

- $~~~~~~~~~~$ $bestAction \leftarrow \arg \max \limits_{a\in A(s)} \sum \limits_{s’} P(s’|s,a)U [s’]$

- $~~~~~~~~~~$ if $bestAction \neq \pi[s]$ then

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $hasChanged$ $\leftarrow$ true

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $\pi[s] \leftarrow bestAction$

- return $\pi$